Posted by Phil Johnson

From The Spectator, 6 January 1872, pp. 10-11.

| The reporter who wrote this account was not impressed with Charles Spurgeon's worldview. "The narrowness of the circle of Mr. Spurgeon's interests in his journey is something stupendous. . . . Every fibre of interest in his mind that was not English was of Hebrew origin. The Bible was his only passport to interest."

The reporter didn't acually hear Spurgeon's lecture; he wrote this account "from a careful reading of two separate reports of it." Nevertheless, it's a fascinating report of Mr. Spurgeon's 1871 journey to Rome. |

|

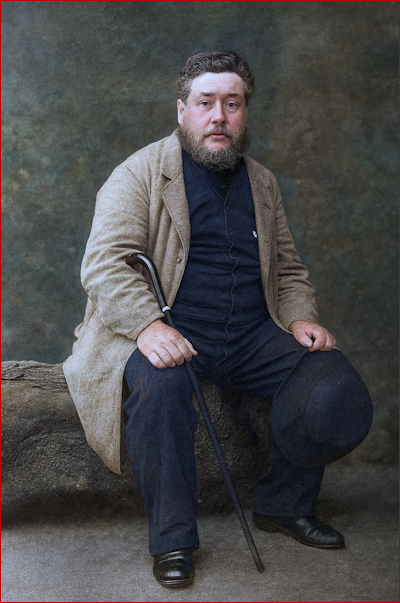

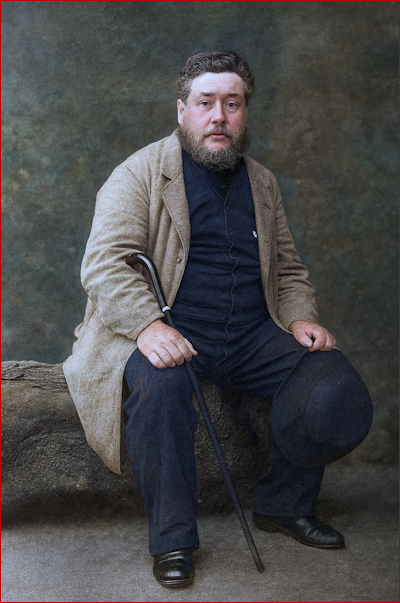

MR. SPURGEON IN ROME

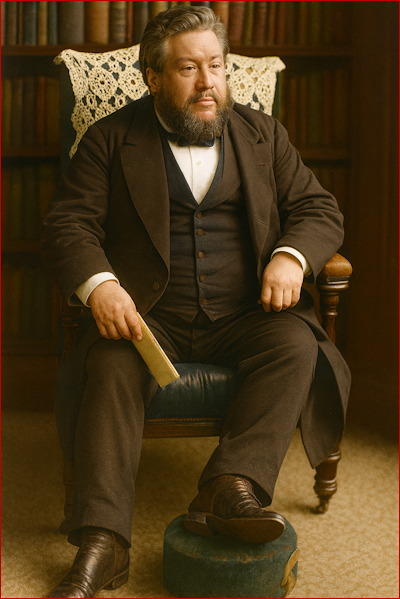

There is a good deal of nature about Mr. Spurgeon. He is not only a very clever and homely preacher, who makes his people realize the wrong and the right in every day's moral alternatives with a vigour and freshness such as few of his class manage to obtain; but he is in himself a very interesting type to study, because he reproduces the ideas of a very large class of English folk with the cleverness and emphasis of a strong nature quite devoid of shyness and reserve. His lecture on his Italian journey to the audience of seven thousand at the Tabernacle on Tuesday was a very remarkable one, if only in this light, that it shows what matters chiefly interested Mr. Spurgeon in his journey to Rome, and interested him so much that he was able to impart that interest quite freshly to his crowded congregation, and also what did not interest him at all. Judging of Mr. Spurgeon's lecture from a careful reading of two separate reports of it, the following appear to have been the chief impressions left on Mr. Spurgeon's memory by his journey.

In Paris he was struck by the crimes of the Commune, and the necessity of enlightened religious teaching to keep down the deadly impulses in every people, the priests having lost their hold on the people of Paris. From Paris he travelled to Dijon, where he was much struck by the short time allowed for dinner in the buffet, and thought it hard that travellers should be shouted at and hurried by railway people, to the great injury of their dinners, without any occasion for the disquietude.

At Lyons he was struck by the cold where he had hoped for warmth, and disgusted with the stoves which sent all the heat up the chimney, "like professing Christians" who spread no warmth around them, but send all their heat up the chimney too. At Marseilles he got completely warm, even in the evening; but what pleased him most was to see the Mediterranean, the sea whereon "the apostle of the Gentiles" sailed, which is beaten by the wind called in the Acts Euroclydon, on which St. Paul was wrecked, and from which he landed near Rome, and perhaps also on the shores of Spain.

The ride from Marseilles to Nice delighted him with its loveliness, with its "rocks on both sides like shot-silk," with its great clumps of olives and its groves of oranges, so full of fruit that you could hardly see the trees for the oranges. The olive trees made him think of Gethsemane, and seemed to be always preaching to him, "We are a type of Jesus," because they would grow on hard lime rock where nothing else would, and "deriving nothing from the hand of man, give him plenty." The oranges he admired, but did not enjoy as fruit,—we suspect he might have said the same of the olives, if he had not magnified them for typical purposes,—being much struck by the superiority of the oranges brought to London, and making the soothing reflection,—"there was no place in the world where they could get things as they could get them in London."

At Nice he was lodged very high up, which he liked because he was near to the roof, on which he could get out, and realize better how Peter felt on the top of the house of Simon the tanner at Joppa. Mr. Spurgeon had not the vision of a vessel let down from heaven with all sorts of beasts, clean and unclean, in it; but he bethought himself seriously on his house-top at Nice, that nothing, even in foreign lands, was "common and unclean," except so far as it is made so by "the thoughts of the heart." One of his fellow travellers was afraid to look much about him, lest he should have his thoughts led away from holiness, but Mr. Spurgeon's feeling was more robust. Fortified by Simon Peter's vision, he looked at Alps and sea, and declared to himself that neither was common or unclean.

However, the idea that foreign countries required some such inspired excuse for being what they are, was evidently not far from him. For instance, the continual washing of clothes at Nice exercised Mr. Spurgeon much, as he did not see many clean clothes, and could not help thinking the people kept one suit of clothes to wear and a separate one to wash, a remark which he improved by a hit at Pharisaic purism and ostentatious observances, so supplementing the stove-smoking analogy for merely "professing" Christians. Mr. Spurgeon was tormented by the mosquitoes, which he called "gnatty little creatures,"—surely such a pun was common, if not unclean,—in spite of his mosquito-curtains, which only shut the mosquitoes in with him, instead of keeping them out, and they seemed to him a type of the cares of the world, which men are always trying to shut out by expedients which only succeed in shutting them in;—in this connection Mr. Spurgeon was hard on the Prussian Palace of Sans Souci at Potsdam, for affecting to be "without care," and he conjectured shrewdly that the said palace only performed the functions of his mismanaged mosquito-curtains at Nice,—we say mismanaged, because a very little care will really suffice to keep mosquitoes out of a mosquito-curtain.

While at Nice Mr. Spurgeon preached on board an American man-of-war, and found a boy who had been brought up in the Newington Schools, and who sent his love by Mr. Spurgeon to his uncle, who was a member—though Mr. Spurgeon had forgotten the name—of the congregation of the Tabernacle. Mr. Spurgeon was duly pleased with the scenery of the Riviera, though he does not describe well. Of Genoa he said nothing except of the remarkable skill in cheating of the Jew population there. Of the Italian railways, he remarked that they were "the slowest things out." He thought the leaning tower of Pisa more crooked even than its reputation, and had evidently an uneasy feeling that it would tumble, and he confessed that it taught him the great superiority of "the straight and square style of building." But Mr. Spurgeon was gratified with the sight of an old baptistery so big as clearly not to be meant "for children," and therefore a testimony to the antiquity of the doctrine of the Baptists.

At Rome he was very cold, and found snow fallen on the morning after his arrival, but he owns that, though quite devoid of superstition, he felt a "thrill" at being there that no other place except Jerusalem would have given him. It was the associations of the place, "which must be felt by any man who has a soul at all." These associations, he goes on to imply, had no connection with republican or mediæval Rome at all.

The Arch of Titus was a memorable thing to stand and look upon. The relief showed Titus returning from the war of Jerusalem with the golden candlesticks and trumpets; and while those things stood there it was idle for infidels to say the Bible was not true. There was the plain history written in stone, and the more such discoveries were made, the more would the truth of the grand old Book be confirmed,"—from which one would suppose both that Mr. Spurgeon had had his doubts as to the historical truth of the siege of Jerusalem before he went to Rome,—or, at least, would have had them, but for hearing of the Arch of Titus,—and that he considers that the siege of Jerusalem, with the carrying off of the golden candlesticks and trumpets, is recorded in the Bible, and not merely prophesied; otherwise the confirmations alleged do not strike us as very telling. As we never yet heard of a sceptic who doubted the one, nor of a believer who affirmed the other, the thrill which ran through Mr. Spurgeon on reaching Rome, so far as it was due to the Arch of Titus, was more creditable to his susceptibility than to his reasoning powers. It was rather of the nature of the stimulus given to the imagination of the Yorkshireman who said he felt as if he had seen London, when he had had a good look at the coachman who drove the London coach the first stage out of York.

Besides the Arch of Titus, Mr. Spurgeon was struck with the Coliseum, especially its size. His own Tabernacle, he said, would have to grow for a thousand years before it reached the same size. He was gratified with the Appian Way, which he described as "the British Museum along both sides of the road for eight miles." He was struck with the evidence of the existence of early Baptists in the Roman catacombs as well as at Pisa, for he found a true Baptistery there also, just as big as the one in the Tabernacle, and he was delighted with a picture of John the Baptist, baptizing our Lord by total immersion.

He was properly shocked at St. Peter's:—"St. Peter's was a church indeed. Looked at from the outside the dome seemed squat, and it had nothing of the glory of our own St. Paul's. But it was a thing that grew upon you; it was so huge and enormous that it filled the soul with awe; you had to grow big yourselves if you would appreciate it, and its excellent proportions. What shocked him was to see the statue of St. Peter there. Some people said it was the statue of Jupiter, and to that it had been replied, if it was not Jupiter it was the Jew Peter, so it did not matter. The amazing thing was to see the people kissing the toe of the statue. His audience might laugh, but it was actually done. He saw gentlemen wiping the toe with their handkerchiefs and kissing it, old women being helped up to do the same, and little children lifted up to follow the example. There also was the chair in which Peter never sat, and people bowing down to pay homage to it. It was, in truth, a big joss-house; an idol shop, and nothing better. It was not the worst image-house in Rome, but it was bad enough, and whatever might be said by those who turned to and professed the Catholic faith, if they were not idolators there were no idolators on earth."

For the rest, Mr. Spurgeon saw the miraculous print of St. Peter's image on the walls of a dungeon in which, according to tradition, he had been confined,—made when he was pushed against it by the brutality of his guards,—saw, and was wroth in his heart. He looked at the Vatican, saw the Papal soldier higher up on the flight of steps than the Italian soldier, who stood sentry at the door, and was convinced,—with about the same cogency of reasoning as that furnished by the Arch of Titus to the truth of the Bible,—that the Papal Government had been the worst on earth; but he had his fears for the stability of the Italian Government, as it had sprung out of a political, and not a religious revolution. Such were Mr. Spurgeon's most vivid memories of his journey to the Eternal City,' and his stay there.

Now, we have two remarks to make on this remarkable record of what this very clever and active-minded preacher did, and, as we may assume, did not, see in this journey, He seems to have seen everything on the surface which he could easily measure by an English standard. His spirit was moved within him at the rain caused by the Communists at Paris, whom he evidently compared with the mobs of London; he was indignant at the needless hurry of his digestion at Dijon, disgusted with the stoves at Lyons, and the gnats and uncleanliness at Nice; could not contain himself about the sluggishness of the Italian railways,—'the slowest things out,'—was overwhelmed with the cunning of the Genoese Jews, amazed at the size of the Coliseum and St. Peter's, and heartily appreciated the Baptizing apparatus of Pisa and the Roman Catacombs. But on the manners, even of the most superficial kind, of the countries he passed through (except in relation to the cleanliness of the clothes, a thoroughly English category of thought), he never seems to have made a single comment, except so far as their religious rites offended him.

There is not a word on the demeanour of the French or Italian peasantry or the bearing of the Roman women, not a remark (in the report at least) on a single piece of famous sculpture or a single great picture, not a memory of the marble palaces of Rome and Genoa, or of the gardens which give so strange a charm to those palaces; not a thought of the secular history of the Italian or Roman republics, not even a reference to Columbus—most English of Italian heroes—at Genoa; not a reference to the Rome of Scipio, or Camel, or Rienzi; not a trace even of the charm of the Campagua or the orthodox delight In the Coliseum by moonlight.

Mr. Spurgeon, though of a remarkably conventional type of character, is utterly unconventional in his want of deference for what be was expected to admire and didn't, and he speaks only of what interested him, and that was, most of all, the idolatry of Rome; next its political independence of the Pope;—then the indications of a sometime Baptist creed still lingering in the Catacombs; and finally, the bigness of one or two Roman buildings, and the Appian Way, because it was by that that St. Paul approached Rome. We cannot help observing that the narrowness of the circle of Mr. Spurgeon's interests in his journey is something stupendous. The mosquitoes and the slow trains evidently made much more impression on him than the soft or stately manners of the Southern peoples, than the grandeur of a world of art entirely new to him, than the associations of places with events which have made history what it is. If Mr. Spurgeon had visited Syria instead of Italy, he would have known much better what he cared to see; but he would probably have described the solitaries of the Lebanon,—the nearest approach he could find to the Elijah and Elisha of Mount Carmel,—in words rather more contemptuous than he applied to the Roman monks; and would certainly have considered the Arab Sheik—his best type for Abraham or Chedorlaomer—one of the "slowest things out" in the way of social intercourse.

The next remark we have to make is that whatever there is of real fascination for Mr. Spurgeon in the journey he undertook, was not given to it by interest in Italian literature, but by interest in Hebrew literature,—that such tincture of universal history as he had at all, was evidently real to him only in connection with the Bible. At Nice he cared to be on the roof of his hotel, because it reminded him of Peter's trance on the roof of the house at Joppa; the blue waters of the Mediterranean interested him so much because they had been swept by the storms which wrecked St. Paul, and are still, no doubt, liable to be lashed into tempest by the Euroclydon under some other name. The olive-trees reminded him of Gethsemane, and the Appian Way of St. Paul's journey. Every fibre of interest in his mind that was not English was of Hebrew origin. The Bible was his only passport to interest in those Southern peoples; it was not only the spiritualizing, but the humanizing and cultivating element of his knowledge. And as it was with him, so was it evidently with the majority of his seven thousand hearers. Should not this make us pause a very long time before we consent to strike out of our popular education the one element which, for a very large section of the English people, constitutes the only real link between the present and the past, between the North and the South, between the West and the East?

any have failed to understand how everything, from the smallest event to the greatest, can be ordained and fixed, and yet how it can be equally true that man is a responsible being, and that he acts freely, choosing the evil, and rejecting the good.

any have failed to understand how everything, from the smallest event to the greatest, can be ordained and fixed, and yet how it can be equally true that man is a responsible being, and that he acts freely, choosing the evil, and rejecting the good. Many have tried to reconcile these two things, and various schemes of theology have been formulated with the object of bringing them into harmony. I do not believe that they are two parallel lines, which can never meet; but I believe that, for all practical purposes, they are so nearly parallel that we might regard them as being so. They do meet, but only in the infinite mind of God is there a converging point where they melt into one. As a matter of practical, everyday experience with each one of us, they continually melt into one; but, so far as all finite understanding goes, I do not believe that any created intellect can find the meeting-place. Only the Uncreated as yet knoweth this.

Many have tried to reconcile these two things, and various schemes of theology have been formulated with the object of bringing them into harmony. I do not believe that they are two parallel lines, which can never meet; but I believe that, for all practical purposes, they are so nearly parallel that we might regard them as being so. They do meet, but only in the infinite mind of God is there a converging point where they melt into one. As a matter of practical, everyday experience with each one of us, they continually melt into one; but, so far as all finite understanding goes, I do not believe that any created intellect can find the meeting-place. Only the Uncreated as yet knoweth this.

ustification has for its matter and means the righteousness of Jesus Christ, set forth in his vicarious obedience, both in life and death.

ustification has for its matter and means the righteousness of Jesus Christ, set forth in his vicarious obedience, both in life and death.

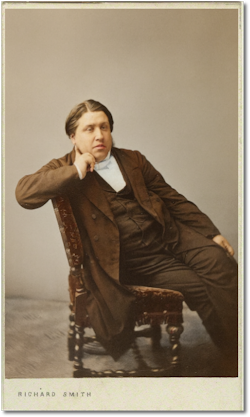

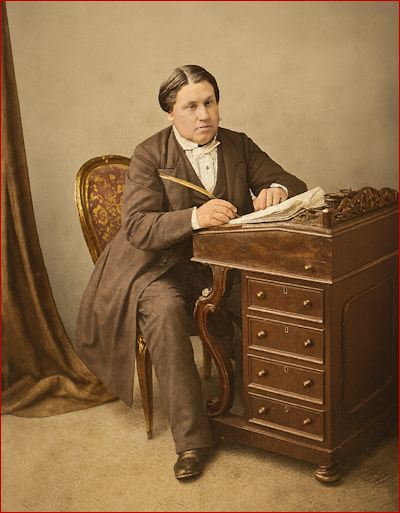

gives of her courtship. The first time she saw her future husband he occupied the pulpit of New Park-street on the Sunday when he preached his first sermon there.

gives of her courtship. The first time she saw her future husband he occupied the pulpit of New Park-street on the Sunday when he preached his first sermon there.

t is not to be thought of for a moment that any minister would appropriate a sermon bodily, and preach it as his own. Such things have been done, we suppose, in remote ages, and in obscure regions; but nobody would justify a regular preacher in so doing. We give great license to good laymen, who are occupied with business all the week, and too much pressed with public engagements to have time to prepare. When princes and peers have speeches made for them, a sort of toleration is understood; and should a public functionary be so anxious to do good that he delivers a sermon, we excuse him if he has largely compiled it; yes, and if he memorises the bulk of it, and bravely says so, we have no word of censure. But for the preacher who claims a divine call, to take a whole discourse out of another preacher's mouth, and palm it off as his own, is an act which will find no defender.

t is not to be thought of for a moment that any minister would appropriate a sermon bodily, and preach it as his own. Such things have been done, we suppose, in remote ages, and in obscure regions; but nobody would justify a regular preacher in so doing. We give great license to good laymen, who are occupied with business all the week, and too much pressed with public engagements to have time to prepare. When princes and peers have speeches made for them, a sort of toleration is understood; and should a public functionary be so anxious to do good that he delivers a sermon, we excuse him if he has largely compiled it; yes, and if he memorises the bulk of it, and bravely says so, we have no word of censure. But for the preacher who claims a divine call, to take a whole discourse out of another preacher's mouth, and palm it off as his own, is an act which will find no defender.

harles Spurgeon loved the Song of Solomon. Sixty-three of his published sermons are based on texts from Solomon's Song. That's two-plus sermons a year on average, twice as many messages as Spurgeon preached from Colossians. In fact, Spurgeon's unabridged Song of Solomon sermons contain enough material to fill a fifteen-hundred-page book with a typeface smaller than you are now reading. All that material was drawn from an Old Testament poetic love song that most preachers would say is the single most difficult book in Scripture from which to preach.

harles Spurgeon loved the Song of Solomon. Sixty-three of his published sermons are based on texts from Solomon's Song. That's two-plus sermons a year on average, twice as many messages as Spurgeon preached from Colossians. In fact, Spurgeon's unabridged Song of Solomon sermons contain enough material to fill a fifteen-hundred-page book with a typeface smaller than you are now reading. All that material was drawn from an Old Testament poetic love song that most preachers would say is the single most difficult book in Scripture from which to preach. We might quibble with Spurgeon's hermeneutical shortcut, but the point he was ultimately making is not altogether invalid. Marriage is, after all, a picture of Christ and His church (Ephesians 5:22-33). Spurgeon's dogmatic assertion simply echoes the words of the apostle: "This mystery [marriage] is profound, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church" (v. 31). In the preceding verse, Paul had Quoted Genesis 2:24 ("Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh"), which is the original divine mandate for the institution of marriage.

We might quibble with Spurgeon's hermeneutical shortcut, but the point he was ultimately making is not altogether invalid. Marriage is, after all, a picture of Christ and His church (Ephesians 5:22-33). Spurgeon's dogmatic assertion simply echoes the words of the apostle: "This mystery [marriage] is profound, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church" (v. 31). In the preceding verse, Paul had Quoted Genesis 2:24 ("Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh"), which is the original divine mandate for the institution of marriage.

ack in the era when I was blogging on a regular basis, there was a lot of discussion about the ethical propriety of pastors' paying for research and writing from a company like

ack in the era when I was blogging on a regular basis, there was a lot of discussion about the ethical propriety of pastors' paying for research and writing from a company like  I could go on. It seems a lot of unscrupulous hustlers are making money hawking superficial sermons to slothful preachers.

I could go on. It seems a lot of unscrupulous hustlers are making money hawking superficial sermons to slothful preachers. But apparently there are a lot of men filling pulpits in evangelical churches who don't much bother to study the Scriptures for themselves. They use the work of others without attribution and pretend their sermons are the fruit of their own study. Whether they recite full sermons or just steal a paragraph here and there doesn't matter. It is still plagiarism. It is an illegitimate shortcut, and if a preacher does it routinely, in my judgment, he is not qualified to teach.

But apparently there are a lot of men filling pulpits in evangelical churches who don't much bother to study the Scriptures for themselves. They use the work of others without attribution and pretend their sermons are the fruit of their own study. Whether they recite full sermons or just steal a paragraph here and there doesn't matter. It is still plagiarism. It is an illegitimate shortcut, and if a preacher does it routinely, in my judgment, he is not qualified to teach. Almost every website that offers sermon-prep shortcuts for preachers will say things like, "Pastors today are busy with administration, planning, organizing, counseling, and a host of other duties. We can help minimize the time you spend preparing sermons."

Almost every website that offers sermon-prep shortcuts for preachers will say things like, "Pastors today are busy with administration, planning, organizing, counseling, and a host of other duties. We can help minimize the time you spend preparing sermons."